What the C-Suite Can Learn from the Rev. – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” Speech

What can the C-suite learn from the Rev. -Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.? As a speech coach, I’m focusing on one moment in the Reverend King’s career, his “I Have a Dream” speech. Justly celebrated as one of the greatest speeches of the 20th century, the speech becomes even more remarkable when you know that the last 6 minutes of the 16-minute speech were ad-libbed. Why should top executives take note?

When I work with executives on their speaking, few of them could imagine ad-libbing a talk in front of 300,000 people. Weeks typically go into the preparation for speeches to much more modest-sized audiences.

And that’s a good thing. Now, some executives do tell me early in the process, “I don’t want to rehearse, it will make me stale.” But I’ve learned that statement almost always masks a fear of looking less-than-perfect in front of the coach. So instead they exchange that relatively low-stakes risk for the certainty of looking unprepared in front of the real audience.

But what about King? Surely I shouldn’t be then recommending that executives throw the script away when the mood strikes them? What executives need to understand is that the Reverend King had spent the previous several decades preaching every Sunday in a style which helped him hone his improvisational skills. He learned to sense when the congregation was in danger of drifting away, and he learned how to keep an audience electrified with rhetoric and oratorical skills guaranteed to keep the people in front of him hanging on every word.

So there are two lessons from the “I Have a Dream” speech. The first is that, the answer to the question of how much rehearsal is enough in order to be ready when history calls – is “about thirty years of weekly work.”

The second lesson is that executives do need to be prepared to respond in the moment when they sense that an audience is indeed not buying what they’re selling. And to do that as elegantly as King you need to be very well prepared indeed.

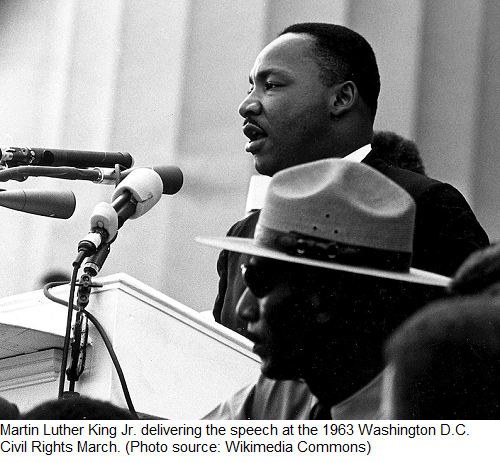

Here’s how it went on the afternoon of August 28, 1963.

At the ten-minute mark, King wrapped up the prepared part of the speech by saying, “No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” This stock Biblical phrase from the Baptist preaching tradition is the signal that King is going off-text, and he next does something truly dramatic: he reaches out to the audience directly, saying, “I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of About thgreat trials and tribulations.”

“Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina,” he continues, and then comes the famous metaphor: “I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment I still have a dream.”

As King works up to the mighty peroration of the greatest American speech of the 20th century, his cadences continue to rise and fall, going higher each time to signal his passion for the subject. The top of the rhetorical arc comes with the closing lines, when King stands on tiptoe, and raises his right hand, and says:

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

The roar from the crowd is unmistakable: King has connected with them, he has given an unforgettable speech, and by digging down deep into his soul, based on years of preparation, he has forever changed the world.