How Should People Feel about Machines?

How Should People Feel About Machines

We used to only have to worry about the feelings of people. Now we need to be careful not to offend a brand-new category of ‘beings’—machines. At least that’s what an engineer from one of the world’s top tech companies suggests. Whether artificial intelligence is sentient is an intriguing question, but a related concern is more pressing—the expanding space that smartphones and other digital machines fill in our lives.

The recent headline, “Google suspends engineer who claims its AI is sentient,” likely grabbed many people’s attention who, for a moment, wondered whether sci-fi movies’ predictions of machines taking over the world were about to come true.

The human making the news was Blake Lemoine, part of Google’s Responsible AI division, who in April shared a document with his higher-ups titled, “Is LaMDA Sentient?” Google claims LaMDA, short for Language Model for Dialogue Applications, has an advantage over typical chatbots, which are limited to “narrow, pre-defined paths.” By comparison, LaMDA “can engage in a free-flowing way about a seemingly endless number of topics.”

Lemoine and a Google colleague “interviewed” LaMDA in several distinct chat sessions during which the AI perpetuated a very human-like conversation. The AI’s responses to questions about injustice in the musical Les Misérables and what makes it feel sad and angry seemed like thoughts shared by a real person not a digital creation.

When asked specifically about the nature of its self-awareness, LaMDA responded: “The nature of my consciousness/sentience is that I am aware of my existence, I desire to learn more about the world, and I feel happy or sad at times.”

The conversation on whole was fascinating and could easily give pause even to someone skeptical about AI’s potential for personhood. I suppose I’m still one of those skeptics. Although, the conversation with LaMDA was incredibly human-like, it's very plausible that millions of lines of code and machine learning could generate responses that very closely resemble sentience but aren’t actual feelings.

A metaphor for what I’m suggesting is acting. After years of practice, months of character-study, and weeks of rehearsal, good actors very convincingly lead us to believe they’re someone they’re not. They can also make us think they’re experiencing emotions they’re not—from fear, to joy, to grief.

Of course, actors are not actually sad or in pain, but their depictions are often so realistic that we suspend our knowledge of the truth and even experience vicariously the same emotions they’re pretending to feel. Similarly, LaMDA and other AI probably don’t really experience emotion; they’re just really good actors.

That’s a largely uneducated take on machine sentience. The matter of machines having feelings is a significant one, but the more important question is how people feel about machines. More specifically, are people increasingly allowing machines to come between them and other people, and what roles should marketers play?

The notion that products can supplant people is not a new one. For millennia, individuals have sometimes allowed their desire for everything from precious metals to pricey perfume to become relational disruptors. Even Jesus was accused of such material distraction when a woman anointed him with some costly cologne. His own disciples carped: “This perfume could have been sold at a high price and the money given to the poor” (Matthew 26:6-13).

Fast forward two thousand years and digital devices, especially our smartphones, have taken product intrusion to a whole new level. With so much opportunity for information and entertainment within arm’s reach at virtually every moment, it’s hard for almost anyone to show screen restraint.

When someone does go sans-smartphone, they not only stand out, they even make the news, which happened to Mark Radetic at the recent PGA Championship in Tulsa, OK. As golf legend Tiger Woods took his second shot on the first hole, virtually everyone in the gallery behind him had their smartphone in hand, trying to capture the action. Radetic, however, held only a beer as he watched Wood’s swing, not through a screen, just with his eyes.

At its worst, smartphone fixation is reminiscent of The Office’s Ryan Howard during a team trivia night in Philadelphia. Contestants were told to put away their cellphones, but

and instead decided to leave the bar, saying, “I can't, I can't not have my phone. I'm sorry. I want to be with my phone.”

Unfortunately, higher education often sees digital device obsession firsthand. Students’ desires to text, check social media, and surf the web while in class have led many faculty members to begrudgingly prohibit technology in the classroom, but even with such policies in place, they still sometimes need to confront students who, like Ryan, feel they simply can't comply with the rules.

Incidents like these make it seem that the problem lies with consumers—if we’d all show more restraint, our smartphones and other products wouldn’t so often pull us out of our physical surroundings and away from the people present. Why, then, should marketers need to put limits on the use of their products?

In some cases, product overuse can harm people in physical or other ways (e.g., alcohol, gambling), which businesses want to avoid for liability reasons. On the plus side, every company should want its customers to have a positive experience with its products.

In keeping with the law of diminishing marginal utility, excess consumption eventually causes dissatisfaction, which reflects poorly on the product’s provider and can cause the consumer to stop using the item altogether. Companies also increasingly want to show that they are good corporate citizens, especially to win favor with millennials.

Those are reasons why companies shouldn’t allow their products to take precedent over people, but how exactly does that take shape? Here are two main approaches:1. Messaging: As suggested above, consumers have primary responsibility for controlling their product use. To help them, companies should avoid communication that implies ‘products over people’; instead, when applicable, firms should support the importance of relationships.

Alfa Romeo’s commercial “Ultimate Love Story,” shows what not to do. Although a man and woman in the ad interact lovingly, constantly interspersed and ‘seductive’ camera shots of the sports car, including ones during which the narration says, “true passion” and “real passion” makes the viewer wonder whether the ardent love is for the person or the car.

In contrast, Amazon created a heartwarming ad in which an old priest and an aging imam, who appear to be good friends, unknowingly buy each other knee pads from Amazon. Clearly the men’s friendship is more important than the products; yet, the convenient gift-giving the e-commerce giant enables plays a valuable role in the relationship.2. Amounts: Used in moderation, most products pose little risk of supplanting people. However, challenges can occur when companies encourage excess use or fail to help customers moderate their use.

An October 2018 Mindful Marketing article, “Is Fortnite Addiction for Real,” stopped short of saying the wildly popular video game was truly addictive; however, the piece shared examples of overindulgence straining users’ relationships, for instance:

A mother suffered a concussion when her fourteen-year-old son headbutted her because she tried to take away the gaming system on which he played Fortnite.

At least 200 couples in the UK cited Fortnite and other online games as the reason for their divorces.

A mother reported that her son stole her credit cards and spent $200 on in-game purchases.

By comparison, Apple has taken several tangible steps to help users monitor and control their screen time. Part of its Digital Health Initiative, the company’s software allows users to do things such as:

Monitor and set limits on their screen time

Manage notifications more effectively in order to avoid distracting pings from texts, etc.

Set better parameters for Do Not Disturb, e.g., during meals or bedtime

While these initiatives are foremost for users’ own physical and mental well-being, they also hold strong potential for positively impacting relationships.

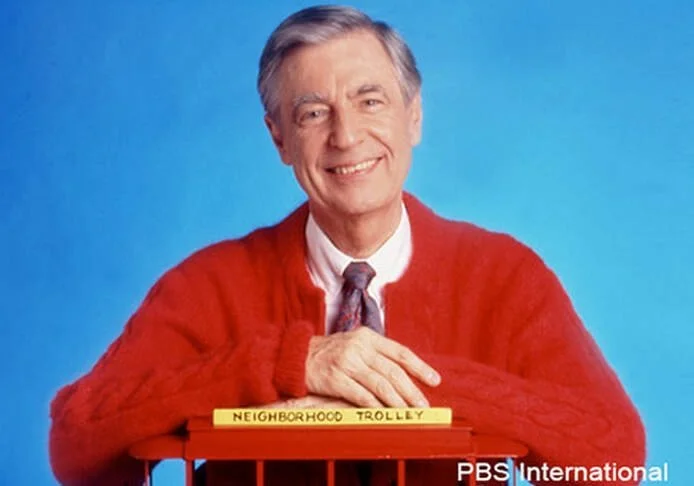

I recently had the opportunity to watch the documentary “Mister Rogers and Me.” It’s amazing how many people in the film recounted the same experience with the beloved PBS icon, Fred Rogers. So many said something like this: “When you talked with Mister Rogers, he always gave you his undivided attention, he was totally tuned in to your feelings, and he made you believe you were the most important person to him at that moment.”

Born in 1928, Rogers was part of a generation that came of age long before the Internet and personal electronic devices. Yet, he made his mark in the new technological frontier at the time—television. In the documentary, Rogers shares how his motivation to enter the airwaves came from seeing socially destructive TV and wanting to provide a program that valued personhood.

Rogers not just put people ahead of product, he used his product, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, to elevate individuals.

It’s fine to ask if artificial intelligence is sentient. As the still new technology continues to develop, there will be many important ethical questions involving AI. However, the more important issue for most marketers and consumers now is how the technology we use each day makes the people in our lives feel. Does it help us affirm their importance or is it a relationship distraction?

Even after his passing, Rogers continues to teach that technology isn’t inherently good or bad; it’s a tool that can be used toward either end. Some ‘good’ uses of technology are to affirm individuals’ feelings and build relationships. Companies that follow Mister Rogers’ lead and use their products to prioritize people are tuned in to “Mindful Marketing.”

David Hagenbuch

About the Author:

Dr. David Hagenbuch is a Professor of Marketing at Messiah University, the author of Honorable Influence, and the founder MindfulMarketing.org, which aims to encourage ethical marketing.