Zero to 66,000 COVID Fatalities in the First 63 Days

Excerpt from The Trump Contagion: How Incompetence, Dishonesty, and Neglect Led to the Worst-Handled Crisis in American History.

The first American fatality from COVID-19 was reported on February 29, 2020. By the end of March more than 5,000 Americans would die from the virus. By the end of April, 66,491 Americans would succumb.

It didn’t have to be that way.

The former head of the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense, which was eliminated by President Donald Trump in 2018, said:

“In a health security crisis, speed is essential… the specter of rapid community transmission and exponential growth is real and daunting.”

In other words, a delay in response will have a negative effect on the outcome. And the longer the delay, the disproportionately more negative the effect will be.

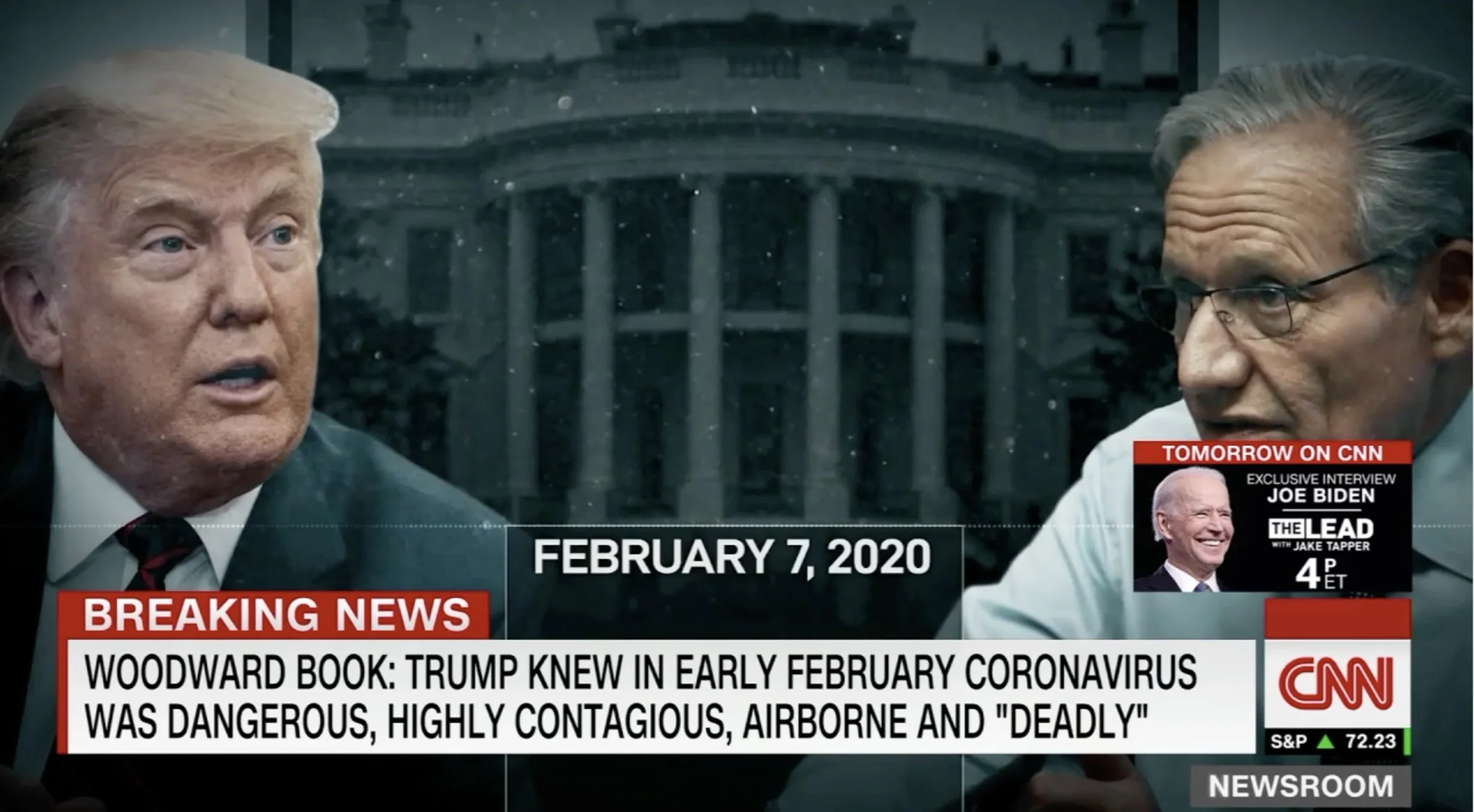

In early February Trump had a telephone interview with Washington Post Associate Editor Bob Woodward, one of 19 telephonic interviews Woodward had with Trump for a book he was writing. Trump told Woodward what he knew about the virus: that it is transmitted through the air, is contracted by breathing the virus, and is “five times more deadly than the flu.”

It was the moment when Trump had the maximum opportunity to control the outcome. This was the moment when a responsible president would share the news with the American people so that they could begin to understand the risks and take precautions. It was a moment to begin a whole-of-government response to address these very real risks.

Trump did neither.

Trump never admitted to the American people what he told Woodward: That the virus is real, deadly, transmitted through air, and contracted by breathing.

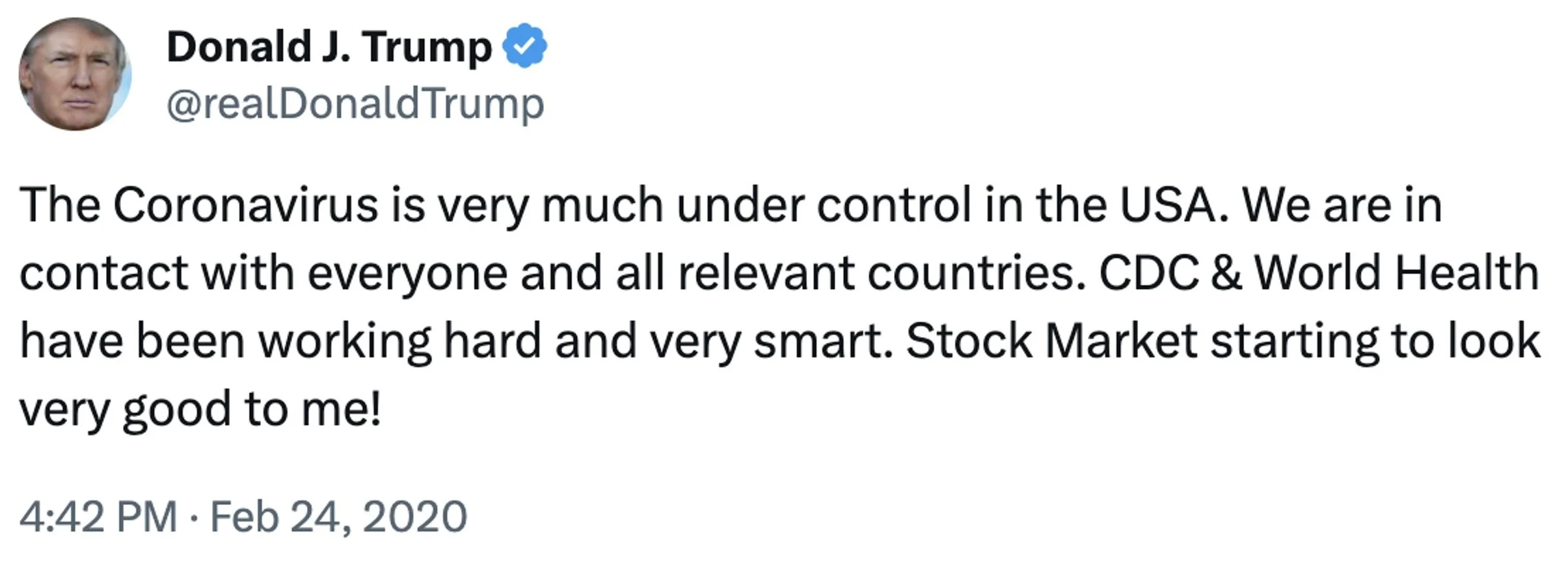

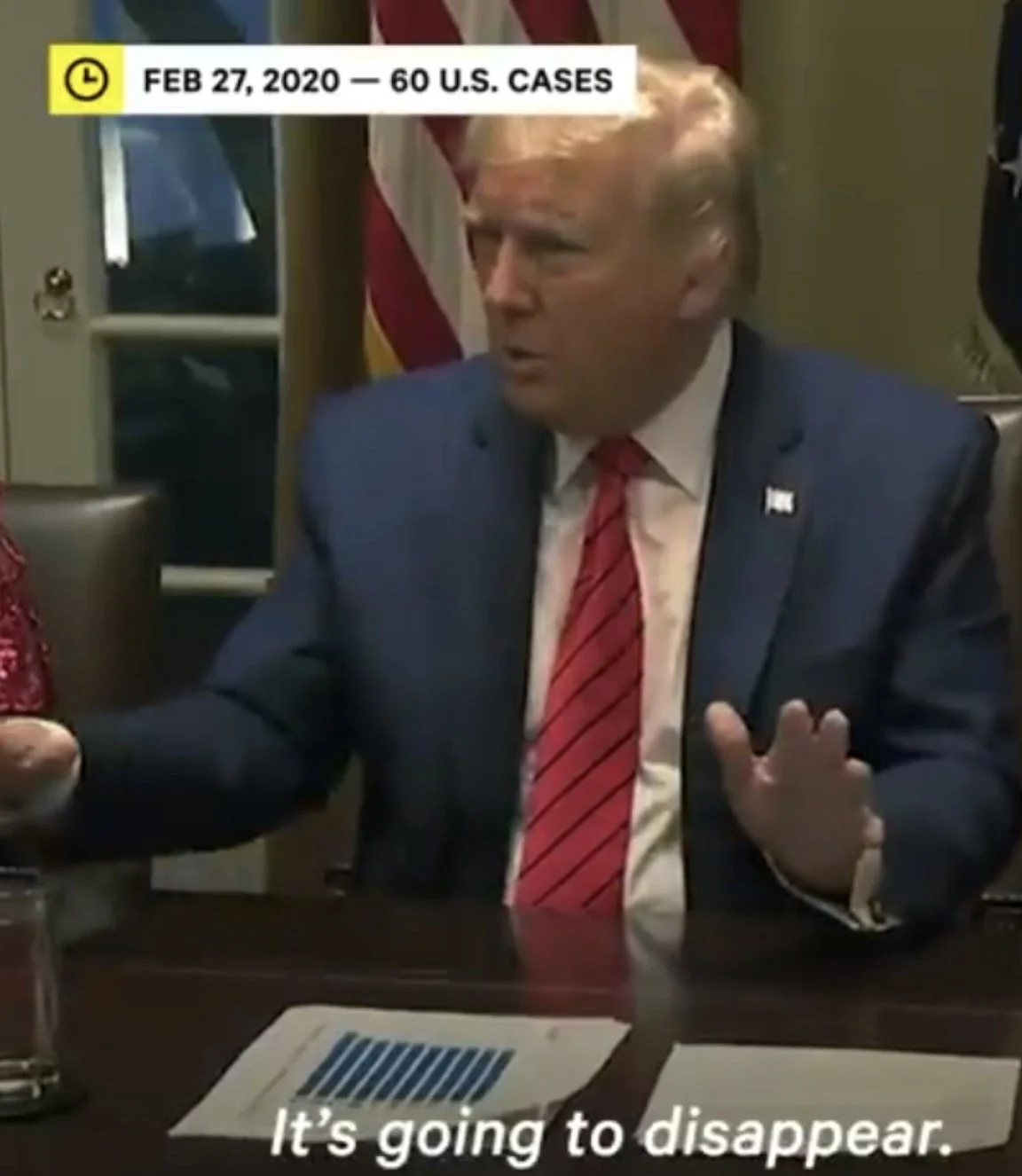

Throughout February and March Trump kept insisting that the virus would simply disappear. He refused to allow the government to follow its own protocols for infectious disease control, including mandating the use of masks to slow the spread.

In the month of March, COVID cases in the United States skyrocketed. On March 2, there were 100 confirmed cases. On March 12, the cases had increased ten-fold to nearly 1,000. By March 19, there were nearly 20,000. By the end of March, there were more than 70,000 cases.

In an earlier CommPro column, I described Dr. Rick Bright, the senior federal career public health official responsible for procuring protective equipment. He tried diligently throughout January and February to persuade the political leadership of the Department of Health and Human Services to surge acquisition of masks and other protective equipment. He was shot down in every attempt. He later told a Congressional hearing:

“They informed me that they did not believe there was a critical urgency to produce masks [sic]… I indicated that we know there will be a critical shortage of these supplies, we need to do something to ramp up production. They indicated that if we notice there is a shortage that we will simply change the CDC guidelines to better inform people who should not be wearing those masks, so that would [sic] save those masks for our healthcare workers. My response was, I cannot believe you can sit and say that with a straight face. That was absurd [sic].”

As Dr. Bright had feared, in early March hospitals and healthcare providers began to raise concerns that they were likely to run out of N95 masks.

But throughout March Trump continued to give false assurances.

On March 11, the World Health Organization declared the global COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.

That same day in New York City, New York University, Fordham University, and Pace University all shut down in-person instruction and began conducting all classes virtually. The next day most other universities in New York City followed suit.

On March 13, Trump declared a national emergency, thereby freeing up $50 billion in emergency funds.

On March 15, after nearly 100 Americans had died, including five in New York City, the city closed all public school buildings and moved to remote learning. New York City also closed all restaurants and bars.

On March 16, with 116 fatalities to date, six counties in California’s Bay Area announced shelter-in-place orders. And governors in affected states were scrambling to acquire the needed protective equipment.

That same day, on a conference call with governors, Trump said that instead of relying on the federal government for personal protective equipment and hospital supplies, states should procure their own supplies. He said,

“Respirators, ventilators, all of the equipment – try getting it yourselves. We will be backing you, but try getting it yourselves.”

The New York Times reported that the suggestion, “… surprised some of the governors, who have been scrambling to contain the outbreak and are increasingly looking to the federal government for help with equipment, personnel, and financial aid.”

The New York Times reported, “The lack of proper masks, gowns and eye gear is imperiling the ability of medical workers to fight the coronavirus – and putting their own lives at risk.”

That week administrators at the New York cancer center Memorial Sloan Kettering told doctors that they had only one week’s supply of respirator masks. One Washington-based hospital chain told The New York Times that it was only a matter of days before some of its dozens of hospitals and hundreds of clinics ran out of masks and other equipment.

The New York Times noted, “‘We are at war with no ammo,’ said a surgeon in Fresno, Calif., who said she had no access to even the most basic surgical masks in her outpatient clinic and has a limited supply of the tight-fitting respirator masks in the operating room.”

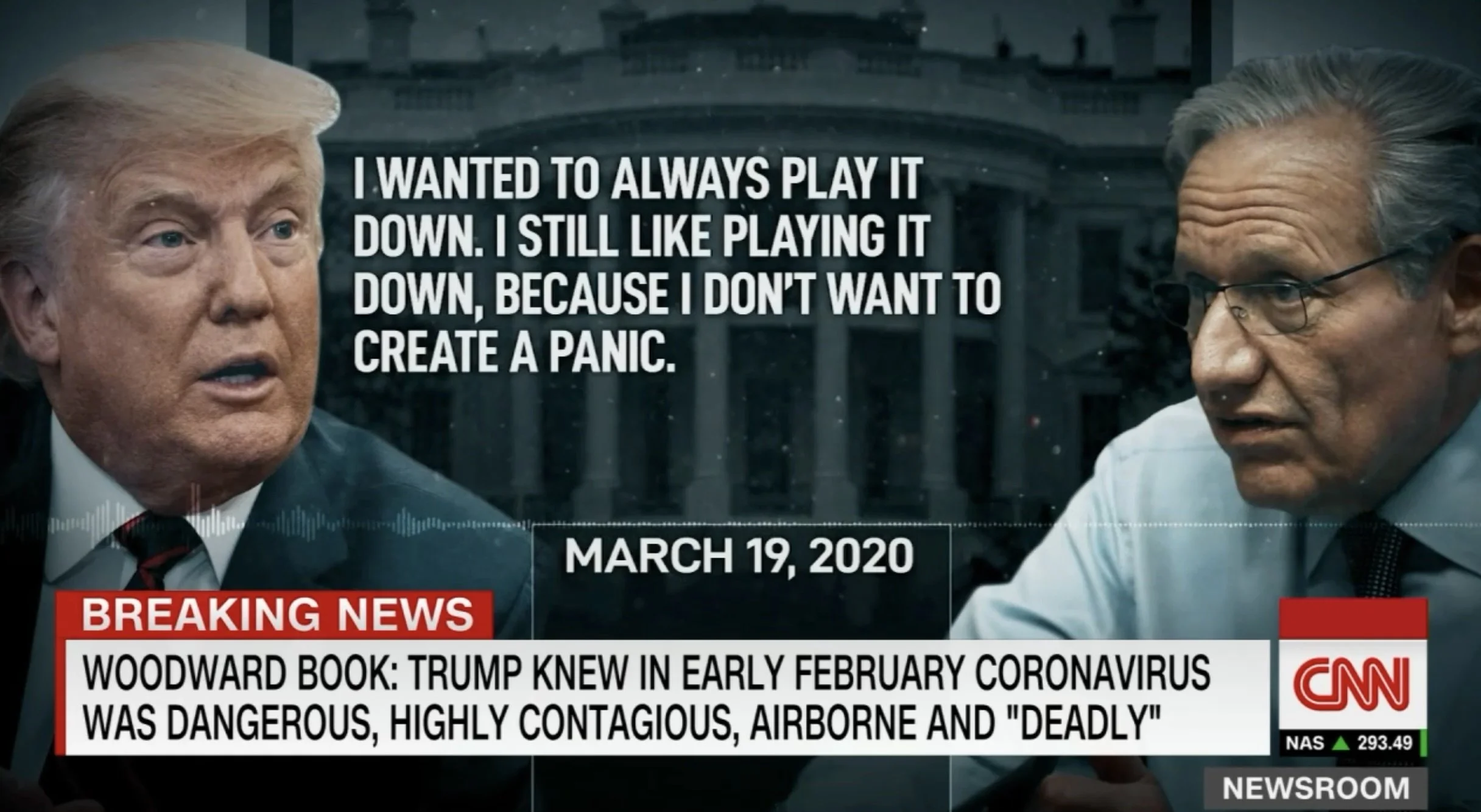

On March 19, when 265 Americans had died of the virus, Trump spoke again with Washington Post Associate Editor Bob Woodward. Woodward asked Trump,

“Was there a moment in all of this, the last two months, where you said to yourself… ‘this is the leadership test of a lifetime’?”

Trump strenuously said that he hadn’t. Woodward seemed surprised. Trump then said that many people had told him so. He added that some had even called him a war-time president.

Woodward asked Trump who had said that first. Trump changed the subject.

He told Woodward what he had learned about the virus: that it is airborne, contracted through breathing; that’s it’s five times more deadly than, “even your most strenuous flus; isn’t just older people who can catch it, but young people can as well.”

Woodward asked Trump to describe what he assumed was a pivot in Trump beginning to take the virus seriously. He asked,

“A moment of talking to somebody, going through this with [Dr. Anthony] Fauci, or somebody who kind of caused a pivot in your mind... to ‘Oh my God, the gravity is almost inexplicable and unexplainable.’”

Trump replied, “Well, I think Bob, really, to be honest with you, I wanted to, I wanted to always play it down. I still like playing it down because I don’t want to create a panic.”

When I heard that response when the audio became public in September 2020, I was initially puzzled. Trump has had no problem creating panic in other contexts: about purported invasions at the southern border, about the need to ban all Muslims from entering the country. What was his hesitation this time?

On looking into this further, I concluded that the panic he was trying to prevent was in the stock market. On the day he spoke with Woodward, March 19, 2020, the S&P stock index had fallen 34 percent from just a month before, on its way to the worst first quarter since 1987. Throughout the year Trump kept pointing to the stock market as the measure of his success. It’s clear from Trump’s response that his playing down the severity of the pandemic was a signal to the stock market and an attempt to maintain public support for his re-election.

By the end of March more than 5,381 Americans had died of the virus and more than half of all Americans were living under stay-at-home orders. But the virus spread more rapidly in April, taking another 60,000 lives.

CNN noted that Trump pushed back on reporters who questioned the effectiveness of the government’s response:

“Trump grew increasingly irate as reporters probed the timeline of his response, claiming the criticism wasn’t fair and that he’d handled the outbreak effectively. ‘Everything we did was right,’ Trump insisted after an extended tirade against negative coverage.”

The hardest-hit part of the United States in April was New York City. The first confirmed case in the city was on March 1. By the end of March, 23,000 cases had been confirmed and 325 New Yorkers had died.

One week later New York City had 72,000 confirmed cases and 2,475 fatalities.

By then, hospitals in New York City were at or near capacity. Emergency field hospitals were set up around the city. Morgues were also full, so refrigerator trucks were stationed outside of some hospitals and the Medical Examiner’s office. The U.S. Navy hospital ship Comfort docked in New York Harbor. And there were discussions of using the city parks to dig temporary mass graves.

Mayor Bill de Blasio told the news media, “If we need to do temporary burials to be able to tide us over to pass the crisis, and then work with each family on their appropriate arrangements, we have the ability to do that. We may well be dealing with temporary burials so we can deal with each family later.”

By mid-April New York City was experiencing 1,000 COVID-19 deaths daily. By April 30 more than 24,000 New Yorkers had died of the disease. That was 36 percent of all U.S. fatalities to date – 66,491.

It didn’t need to be this way.